Life span, the period of time between

the birth and death of an organism.

It is a commonplace that all

organisms die. Some die after only a brief existence, like that of the mayfly,

whose adult life burns out in a day, and others like that of the gnarled

bristlecone pines, which have lived thousands of years. The limits of the life

span of each species appear to be determined ultimately by heredity. Locked

within the code of the genetic material are instructions that specify the age

beyond which a species cannot live given even the most favourable conditions.

And many environmental factors act to diminish that upper age limit.

Measurement of Life Span

The maximum life span is a

theoretical number whose exact value cannot be determined from existing

knowledge about an organism; it is often given as a rough estimate based on the

longest-lived organism of its species known to date. A more meaningful measure

is the average life span; this is a statistical concept that is derived by the

analysis of mortality data for populations of each species. A related term is

the expectation of life, a hypothetical number computed for humans from

mortality tables drawn up by insurance companies. Life expectancy represents

the average number of years that a group of persons, all born at the same time,

might be expected to live, and it is based on the changing death rate over many

past years.

The concept of life span implies that

there is an individual whose existence has a definite beginning and end. What

constitutes the individual in most cases presents no problem: among organisms

that reproduce sexually the individual is a certain amount of living substance

capable of maintaining itself alive and endowed with hereditary features that

are in some measure unique. In some organisms, however, extensive and

apparently indefinite growth takes place and reproduction may occur by division

of a single parent organism, as in many protists, including bacteria, algae,

and protozoans. If these divisions are incomplete, a colony results; if the

parts separate, genetically identical organisms are formed. In order to

consider life span in such organisms, the individual must be defined

arbitrarily since the organisms are continually dividing. In a strict sense,

the life spans in such instances are not comparable to those forms that are

sexually produced.

The beginning of an organism can be

defined by the formation of the fertilized egg in sexual forms; or by the

physical separation of the new organism in asexual forms (many invertebrate

animals and many plants). In animals generally, birth is considered to be the

beginning of the life span. The timing of birth, however, is so different in

various animals that it is only a poor criterion. In many marine invertebrates

the hatchling larva consists of relatively few cells, not nearly so far along

toward adulthood as a new-born mammal. For even among mammals, variations are

considerable. A kangaroo at birth is about an inch long and must develop

further in the pouch, hardly comparable to a new-born deer, who within minutes

is walking about. If life spans of different kinds of organisms are to be

compared, it is essential that these variations be accounted for. The end of an

organism’s existence results when irreversible changes have occurred to such an

extent that the individual no longer actively retains its organization. There

is thus a brief period during which it is impossible to say whether the

organism is still alive, but this time is so short relative to the total length

of life that it creates no great problem in determining life span.

Some organisms seem to be potentially

immortal. Unless an accident puts an end to life, they appear to be fully

capable of surviving indefinitely. This faculty has been attributed to certain

fishes and reptiles, which appear to be capable of unlimited growth. Without

examining the various causes of death in detail (see death) a distinction can

be made between death as a result of internal changes (i.e., aging) and death

as a result of some purely external factor, such as an accident. It is notable

that the absence of aging processes is correlated with the absence of

individuality. In other words, organisms in which the individual is difficult

to define, as in colonial forms, appear not to age.

Plants

Plants grow old as surely as do

animals. However, a generally accepted definition of age in plants has not yet

been realized. If the age of an individual plant is that time interval between

the reproductive process that gave rise to the individual and the death of the

individual, the age attained may be given readily for some kinds of plants but

not for others.

Problem of defining age

An English oak that has 1,000 annual

rings in the trunk is 1,000 years old. But age is less certain in the case of

an arctic lupine that germinated from a seed that, containing the embryo, had

been lying in a lemming’s burrow in the arctic permafrost for 10,000 years.

The mushroom caps that appear

overnight last for only a few days, but the network of fungus filaments in the

soil (the mycelia) may be as old as 400 years. Because of important differences

in structure, the life span of higher plants cannot be compared with that of

higher animals. Normally, embryonic cells (that is, cells capable of changing

in form or becoming specialized) cease to exist very early in the life of an

animal. In plants, however, embryonic tissue—the plant meristems—may contribute

to growth and tissue formation for a much longer time, in some cases throughout

the life of the plant. Thus the oldest known trees, bristlecone pines of

California and Nevada, have one meristem (the cambium) that has been adding

cells to the diameter of these trees for, in many cases, more than 4,000 years

and another meristem (the apical) that has been adding cells to the length of

these trees for the same period. These meristematic tissues are as old as the

plant itself; they were formed in the embryo. The wood, bark, leaves and cones,

however, live for only a few years. The wood of the trunk and roots, although

dead, remains a part of the tree indefinitely, but the bark, leaves, and cones

are continually in the process of dying and sloughing off.

Among the lower plants only a few

mosses possess structures that enable an estimate of their age to be made. The

haircap moss (Polytrichum) grows through its own stem tip each year, leaving a

ring of scales that marks the annual growth. Three to five years’ growth in

this moss is common, but life spans of 10 years have been recorded. The lower

portions of such a moss are dead, though intact. Peat moss (Sphagnum) forms

extensive growths that fill acid bogs with a peaty turf consisting of the dead

lower portions of mosses whose living tops continue growing. Mosses that become

encrusted with lime (calcium carbonate) and form “tufa” beds several metres

thick also have living tips and dead lower portions. On the basis of their

observed annual growth, some tufa mosses are estimated to have been growing for

as long as 2,800 years.

No reliable method for determining

the age of ferns exists, but on the basis of size attained and growth rate,

some tree ferns are thought to be several decades old. Some club mosses, or

lycopsids, have a “storied” growth pattern similar to that of the haircap moss.

Under favourable conditions some specimens live five to seven years.

The woody seed plants, such as

conifers and broadleaf trees, are the most amenable to determination of age. In

temperate regions, where each year’s growth is brought to an end by cold or

dryness, every growth period is limited by an annual ring—a new layer of wood

added to the diameter of the tree. These rings may be counted on the cut ends

of a tree that has been felled or, using a special instrument, a cylinder of

wood can be cut out and the growth rings counted and studied. In the far north

growth rings are so close together that they are difficult to count. In the

moist tropics growth is more or less continuous, so that clearly defined rings

are difficult to find.

Often the age of a tree is estimated

on the basis of its diameter, especially when the average annual increase in

diameter is known. The source of greatest error in this method is the not

infrequent fusing of the trunks of more than one tree, as, for example,

occurred in a Montezuma cypress in Santa María del Tule, a little Mexican

village near Oaxaca. This tree, described by the Spanish explorer Hernan Cortés

in the early 1500s, was earlier estimated on the basis of its great thickness

to be 6,000 years old; later studies, however, proved it to be three trees

grown together. Estimates of the age of some English yews have been as high as

3,000 years, but these figures, too, have turned out to be based on the fusion

of close-growing trunks, none of which is more than 250 years old. Increment

borings of bristlecone pines have shown specimens in the western United States

to be 4,600 years old.

Growing season of seed plants

Annuals

Plants, usually herbaceous, that live

for only one growing season and produce flowers and seeds in that time are

called annuals. They may be represented by such plants as corn and marigolds,

which spend a period of a few weeks to a few months rapidly accumulating food

materials. As a result of hormonal changes—brought about in many plants by

changes in environmental factors such as day length and temperature—leaf-producing

tissues change abruptly to flower-producing ones. The formation of flowers,

fruits, and seeds rapidly depletes food reserves and the vegetative portion of

the plant usually dies. Although the exhaustion of food reserves often accompanies

death of the plant, it is not necessarily the cause of death.

Biennials

These plants, too, are usually

herbaceous. They live for two growing seasons. During the first season, food is

accumulated, usually in a thickened root (beets, carrots); flowering occurs in

the second season. As in annuals, flowering exhausts the food reserves, and the

plants die after the seeds mature.

Perennials

These plants have a life span of

several to many years. Some are herbaceous (iris, delphinium), others are

shrubs or trees. The perennials differ from the above-mentioned groups in that

the storage structures are either permanent or are renewed each year.

Perennials require from one to many years growth before flowering. The

preflowering (juvenile) period is usually shorter in trees and shrubs with

shorter life spans than in those with longer life spans. The long-lived beech

tree (Fagus sylvatica), for example, passes 30–40 years in the juvenile stage,

during which time there is rapid growth but no flowering.

Some plants—cotton and tomatoes, for

example—are perennials in their native tropical regions but are capable of

blooming and producing fruits, seeds, or other useful parts in their first

year. Such plants are often grown as annuals in the temperate zones.

Longevity of seeds

Although there is great variety in

the longevity of seeds, the dormant embryo plant contained within the seed will

lose its viability (ability to grow) if germination fails to occur within a

certain time. Reports of the sprouting of wheat taken from Egyptian tombs are

unfounded, but some seeds do retain their viability a long time. Indian lotus

seeds (actually fruits) have the longest known retention of viability. On the

other hand, seeds of some willows lose their ability to germinate within a week

after they have reached maturity.

The loss of viability of seeds in

storage, although hastened or retarded by environmental factors, is the result

of changes that take place within the seed itself. The changes that have been

investigated are: exhaustion of food supply; gradual denaturing or loss of

vital structure by protoplasmic proteins; breakdown of enzymes; accumulation of

toxins resulting from the metabolism of the seed. Some self-produced toxins may

cause mutations that hamper seed germination. Since seeds of different species

vary greatly in structure, physiology, and life history, no single set of age

factors can apply to all seeds.

Animals

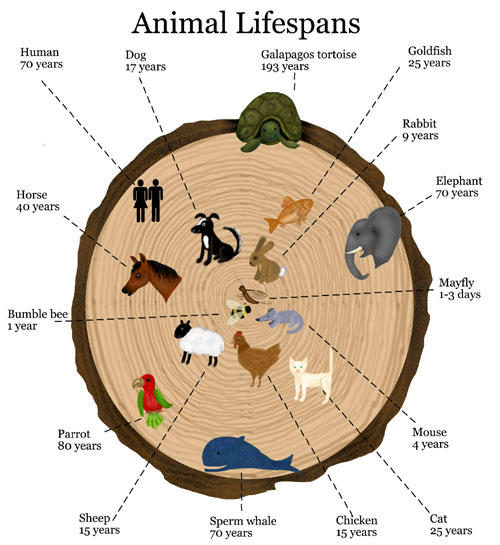

Much of what is known of the length

of life of animals other than man derives from observations of domesticated

species in laboratories and zoos. One has only to consider how few animals

reveal their age to appreciate the difficulties involved in answering the

apparently simple question of how long they live in nature. In many fishes, a

few kinds of clams, and an occasional species of other groups, growth is

seasonal, so that annual zones of growth, much like tree rings, are produced in

some part of the organism. Among game species, methods of determining relative

age by indicators such as the amount of tooth wear or changes in bone structure

have yielded valuable information. Bird bands and other identifying marks also

make age estimation possible. But one of the consequences of the fact that

animals move is that very little is known about the life span of most species

as they exist in nature.

Maximum and average longevity

Many of the extreme claims of

longevity that are occasionally made for one species or another have

consistently been proven false when subjected to critical scrutiny. Although

the maximum life span that has been observed for a particular species cannot be

considered absolute, since a limited number of individuals at best has been

studied, this datum probably provides a fair approximation of the greatest age

attainable for this kind of animal under favourable conditions. Animals in

captivity, which provide most of the records of extreme age, are exposed to far

fewer hazards than those in the wild.

Environmental influences

Life span usually is measured in

units of time. Although this may seem eminently logical, certain difficulties

may arise. In cold-blooded animals in general, the rate of metabolism that

determines the various life processes varies with the temperatures to which

they are exposed. If aging depends on the expenditure of a fixed amount of

vital energy, an idea first proposed in 1908, life span will vary tremendously

depending on temperature or other external variables that influence life span.

There is considerable evidence attesting at least to the partial cogency of

this argument. So long as a certain range is not exceeded, cold-blooded

invertebrates do live longer at low than at high temperatures. Rats in the

laboratory live longest on a somewhat restricted diet that does not permit

maximum metabolic rate. Of perhaps even greater significance is the fact that

many animals undergo dormant periods. Many small mammals hibernate; a number of

arthropods have life cycles that include periods during which development is

arrested. Under both conditions the metabolic rate becomes very low. It is

questionable whether such periods should be included in computing the life span

of a particular organism. Comparisons between species, some of which have such

inactive periods while others do not, are dangerous. It is possible that life

span could be measured more adequately by total metabolism; however, the data

that are necessary for this purpose are almost entirely lacking.

Length of life is controlled by a

multitude of factors, which collectively may be termed environment, operating

on a genetic system that determines how the individual will respond. It is

impossible to list all the environmental factors that may lead to death. For

analytical purposes it is, however, useful to make certain formal separations.

Every animal is exposed to (1) a pattern of numerous events, each with a

certain probability of killing the individual at any moment and, in the

aggregate, causing a total probability of death or survival; (2) climatic and

other changes in the habitat, modifying the frequency with which the various

potentially fatal events occur; and (3) progressive systemic change, inasmuch

as growth, reproduction, development, and senescence are characteristics

intrinsic in the organism and capable of modifying the effects of various environmental

factors.

Patterns of survival

Consider a group of similar animals

of the same age. Although no two individuals can have precisely the same

environment, let it be assumed that the environment of the group remains

effectively constant. If the animals undergo no progressive physiological

changes, the factors causing death will produce a death rate that will remain

constant in time. Under these conditions, it will take the same amount of time

for the population to become reduced to one-half its former number, no matter

how many animals remain at the beginning of the period considered. The animals

therefore survive according to the pattern of an accident curve. This is the

sense in which many of the lower animals are immortal. Although they die, they

do not age; how long they have already lived has no influence on their further

life expectation.

Another group of animals may consist

of individuals that differ markedly in their responses to the constant

environment. They may be genetically different, or their previous development

may have caused variations to arise. Those individuals that are most poorly

suited to the new environment will die, leaving survivors that are better

adapted. The same result can also be achieved in other ways. If the environment

varies geographically, those individuals that happen to find areas in which

existence can be maintained will survive, while the remainder will die. Or, as

a result of their own properties, animals in a constant environment may

acclimate in a variety of ways, thus adjusting to the existing conditions. The

pattern of survival that results in each of these cases is one in which the

death rate declines with time, as illustrated by the selection–acclimation

curve.

In the absence of death from other

causes, all members of a population may exist in their environment until the

onset of senescence, which will cause a decline in the ability of individuals

to survive. In a sense they can be considered to wear out as does a machine.

Their survival is best described by individual differences among members of the

population that determine the curvature of the survival line (wearing-out

curve). The more the population varies, the less abrupt is the transition from

total survival to total death.

Under the actual conditions of

existence of animals the three types of survival (accident pattern,

selection–acclimation pattern, wearing-out pattern) above all enter as

components of the realized survival pattern. Thus in animals that are carefully

maintained in the laboratory, survival is approximately that of the wearing-out

pattern. Environmental accidents can be kept to a minimum under these

conditions, and survival is almost complete during the major part of the life

span. In all known cases, however, the early stages of the life span are

characterized by a noticeable contribution of the selection–acclimation

pattern. This must be interpreted as a result of developmental changes that

accompany the early life of the individuals and of selective processes that

operate on those organisms whose genetic constitutions are ill fitted for that

environment.

In some of the larger mammals in

nature, the existing evidence points to a similar survival pattern. In a

variety of other animals, however, and including fishes and invertebrates,

mortality in the young stages is so high that the selection–acclimation curve

predominates. One estimate places the mortality of the Atlantic mackerel during

its first 90 days of life as high as 99.9996 percent. Since some mackerel do

live for several years, a mortality rate that decreases with age is indicated.

Similar considerations probably apply to all those animals that have larval

stages that serve as dispersal mechanisms.

When the postjuvenile portion of the

life span is considered by itself, a number of animals for which such

information has been gathered—including primarily fishes and birds—have

survivorship curves that are dominated by the accident pattern. In these species

in nature, death from old age apparently is rare. Their chance of surviving to

an advanced age is so small that it may be statistically negligible. In modern

times, human predation is a large factor in the mortality of these species in

many cases. Since deaths from fishing and hunting are largely independent of

age, once an animal has reached a certain minimum size, such a factor only

makes the survival curve steeper but does not change its shape. One consequence

of such increased mortality is that fewer old and large individuals are noticed

in a population.

More complex survival patterns, such

as the hypothetical one illustrated, undoubtedly exist. They should be looked

for in those species in which extensive reorganization of the animal is part of

the normal life cycle. In effect, these animals change their environment

radically, in some cases several times during a lifetime. The frog offers a

familiar example. During its period of early development and until shortly

after hatching, the animal is subject to major internal, and some external,

change. As a tadpole it is adjusted to an aquatic, herbivorous life. The

metamorphosis to the terrestrial, carnivorous adult form is accompanied by

varied physiological stresses that must be expected to produce a temporary

increase in mortality rate. In some insects the eggs, larvae, pupae, and adults

are exposed to and respond to quite different environments, and a survivorship

pattern even more complex than that described by the composite curve may exist.

The same species will exhibit changed

survival in different environments. In captivity an animal population may

approach the wearing-out pattern; in its natural habitat survivorship may vary

with age in a quite different way. Although one can assign a maximum potential

life span to an individual—while realizing that this maximum may not be

attained—it is impossible to specify the survivorship pattern unless the

environment is also specified. This is another way of saying that life span is

the joint property of the animal and the environment in which it lives.

Comments

Post a Comment